The Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum is an oft recommended destination for family day trips and romantic dates, with its awe-inspiring displays of towering dinosaur skeletons and quaint collections of delicately shimmering insects. What most visitors don’t know about is the vast archives containing hundreds of thousands of specimens hidden only a few floors above. The collections of natural history museums are rarely limited to what visitors can see. Dedicated to cutting edge research, they also serve as a storage space for specimens collected, and as a research facility for the scientists studying them. In this six-part feature, we’ll take you on a virtual tour of what goes on behind those closed doors. Let’s take a look at the hoard!

The first stop is the Cryogenic Collection, located not within the museum’s main building, but in an unassuming office beneath the old Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research (RMBR), just underneath the Science Library in the Faculty of Science, within the National University of Singapore (NUS) campus.

You’ll probably recognise the term “cryo” from science fiction stories, like Interstellar, where the astronauts preserve their bodies by entering long term “cryosleep”. Stemming from Greek origins, the term “cryo” means “cold”, while “genic” means “having to do with production”. Calling the cryogenic collection “cold” would be a gross understatement, though.

These giant vats are filled with liquid nitrogen, which as you may know, is very, very cold. In fact, liquid nitrogen boils at 77.09 Kelvin, or -196 degrees Celsius. The contents of the cryogenic collection themselves are kept in a cloud of evaporated nitrogen vapour at around -178 to -190 degrees Celsius.

Much in the same way the dinosaur embryos were preserved in Jurassic Park, the nitrogen vats (affectionately nicknamed Humpty and Dumpty) protect the blood and tissue samples stored within them from degrading – pretty much forever. These samples are not completely submerged in liquid nitrogen. Instead, they are stored in little tubes and racks, which are then stacked in neat little towers within the vats. A pool of liquid nitrogen at the bottom of the vat evaporates, which produces a cooling effect that keeps the environment extremely cold.

Those cute strawberry shaved ice colours? Yup, it’s blood.

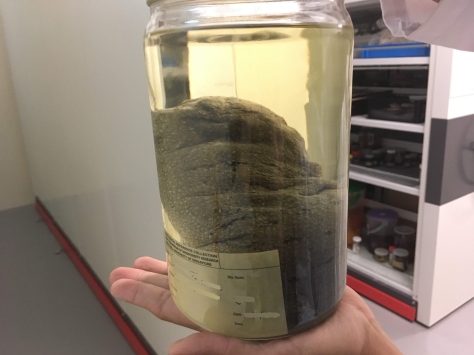

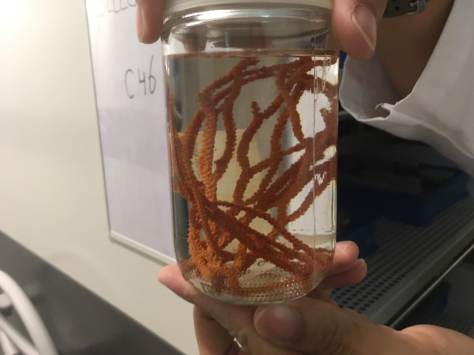

Now, what’s so precious about some bits of blood and tissue? We can keep the bodies of specimens in cupboards and jars to study their physical appearance, but the preservation process sometimes involves the use of formalin and denatured ethanol, chemicals which aren’t great for preserving the DNA within. Tiny amounts of blood and tissue are enough to serve as a record of the genetic makeup of the organisms we need to study. The museum’s cryogenic collection mostly contains genetic records of species found in Southeast Asia, including some from Singapore, such as Sunda pangolins, Smooth-coated otters, and the locally endangered Raffles’ Banded Langur. With more genetic data from these animals, we can compare how certain aspects of their DNA vary from individual to individual, or how they change over time. This can ultimately inform future conservation efforts.

Right to left: Sunda Pangolin, Smooth-coated otter, Raffles’ Banded Langur, all native to Singapore.

Right to left: Sunda Pangolin, Smooth-coated otter, Raffles’ Banded Langur, all native to Singapore.

Each blue tray contains about a hundred specimens, and each tower contains twelve trays. That adds up to over twenty thousand samples, and the vat isn’t even full yet! (By the way, Humpty is still empty.) The future is indeed bright for these cold boys. Oh, and I also had the pleasure of meeting their roommates Fat Boy, Skinny Girl, Olaf, Jack Frost, and Freya, who are all freezers. It’s a full house in here.

With so many friends, the curator never gets lonely.

Keep reading to continue our tour of the natural history museum!

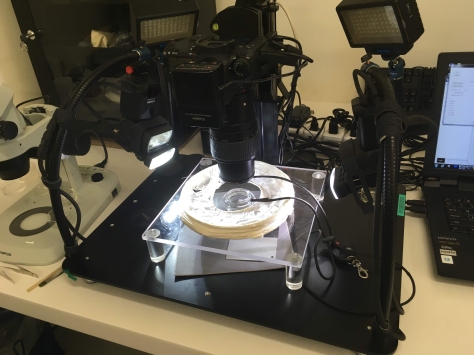

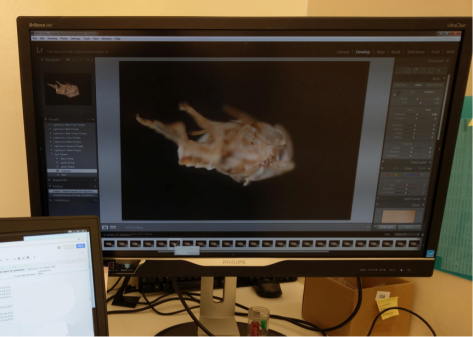

I promise you there’s a specimen on that dish. Just keep squinting. Or look over here:

I promise you there’s a specimen on that dish. Just keep squinting. Or look over here:

This article is brought to you by entosupplies.com – I wish.

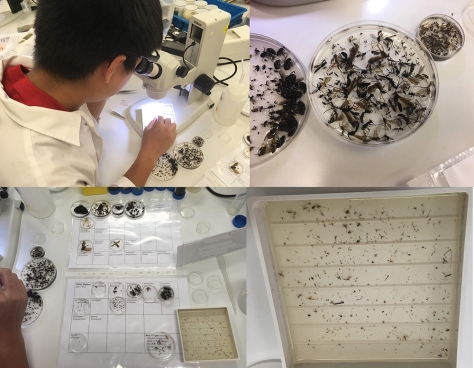

This article is brought to you by entosupplies.com – I wish. More legs, more work.

More legs, more work.

Let’s all pray for Spencer’s eyes.

Let’s all pray for Spencer’s eyes.

Don’t panic, those are just unfortunately placed barnacles.

Don’t panic, those are just unfortunately placed barnacles.

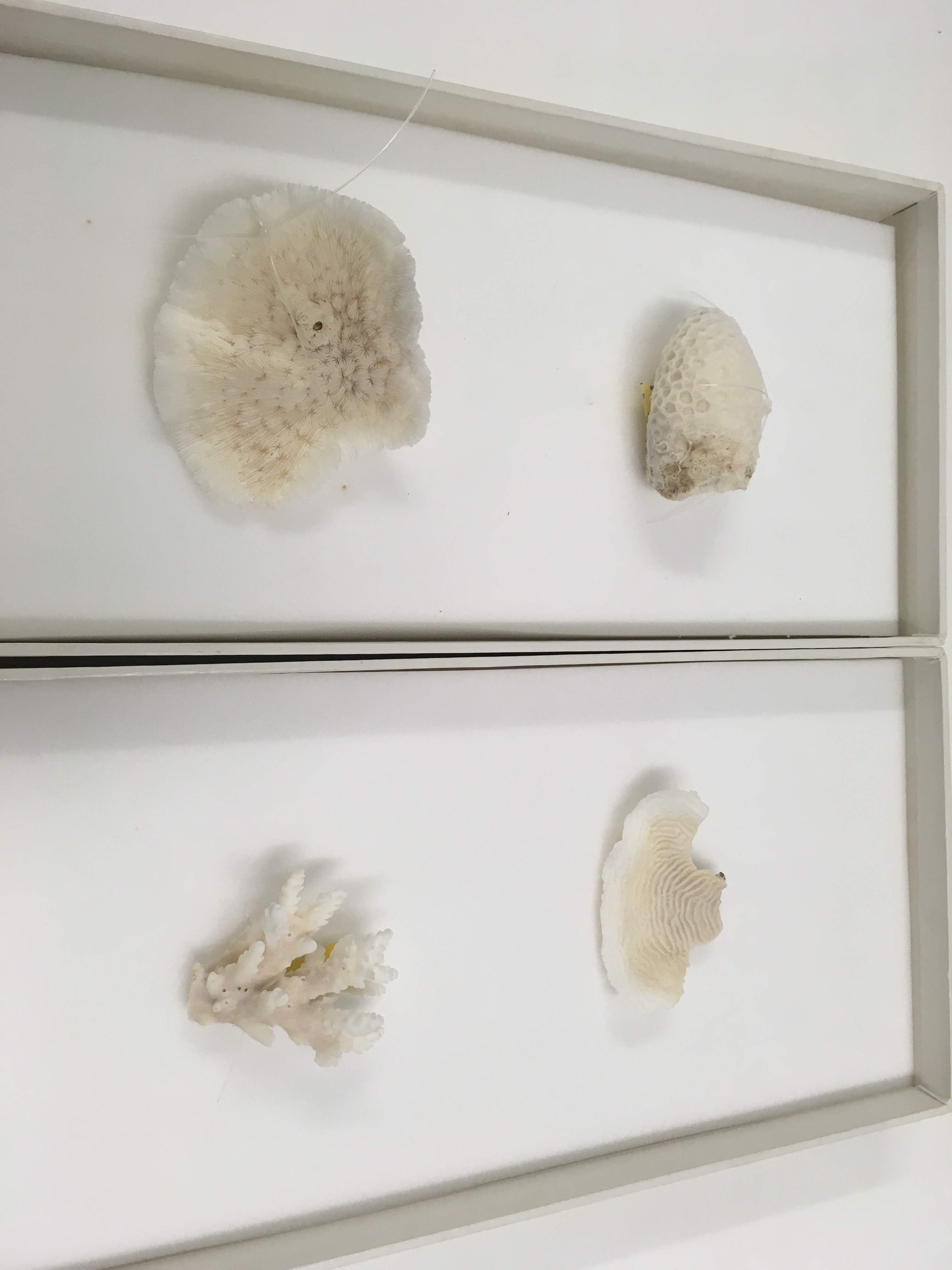

I stole this and it looks great on my coffee table. Just kidding.

I stole this and it looks great on my coffee table. Just kidding.

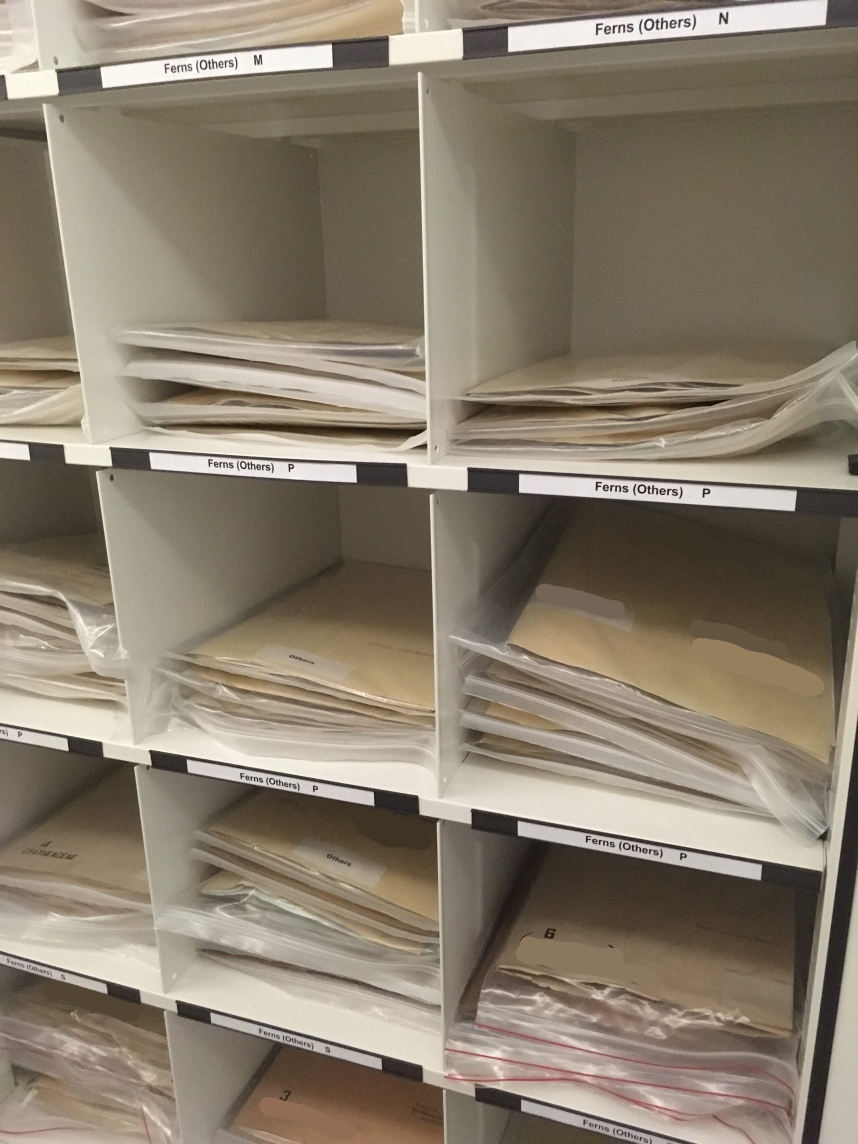

I’d say this is a good place for an Instagram photoshoot.

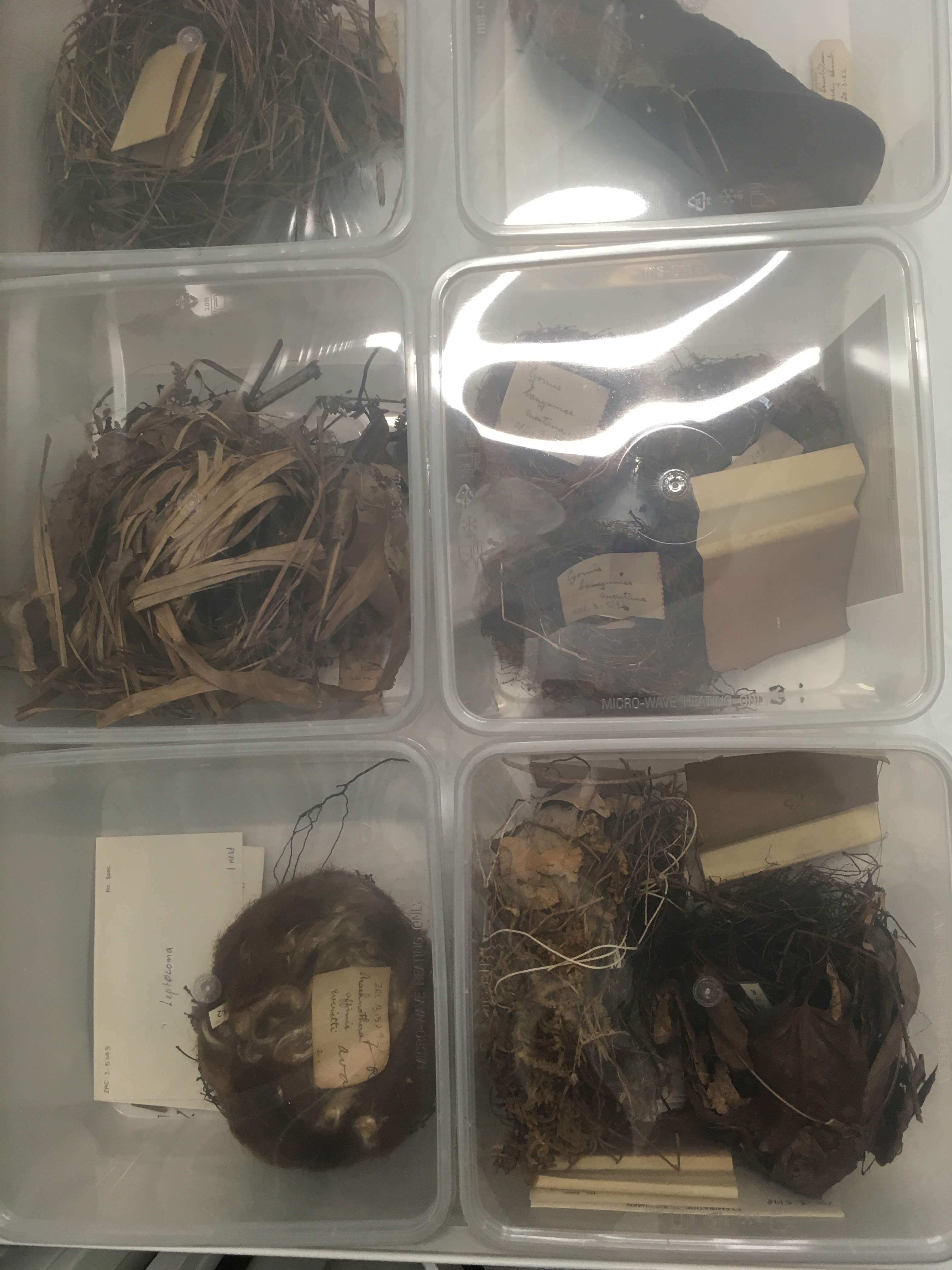

I’d say this is a good place for an Instagram photoshoot. Birds, mammals, sea shells, eggs, even nests! Even poop! Scientists really go for anything, huh?

Birds, mammals, sea shells, eggs, even nests! Even poop! Scientists really go for anything, huh?

Objectively? Probably the coolest drawers you’ll ever pull open.

Objectively? Probably the coolest drawers you’ll ever pull open.

Right to left: Sunda Pangolin, Smooth-coated otter, Raffles’ Banded Langur, all native to Singapore.

Right to left: Sunda Pangolin, Smooth-coated otter, Raffles’ Banded Langur, all native to Singapore.